On her changed relationship to money and the barriers to earning and learning faced by women in media

A short while ago I had the pleasure and privilege to talk to Annie Nightingale CBE, the legendary BBC broadcaster.

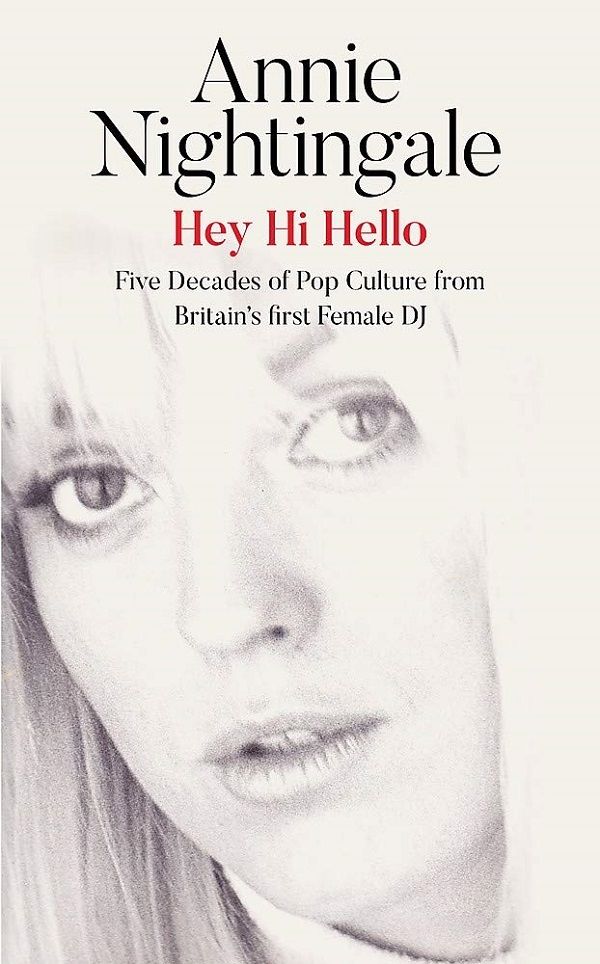

The interview took place last year around the promotion of Nightingale’s excellent 2020 book ‘Hey Hi Hello’ – a collection of stories gathered across 50 years at the heart of pop culture. During our discussion, I explained to Nightingale what I’m trying to do here with Creative Money and she was kind enough to answer some questions about her trailblazing career, how she views money and her thoughts on overcoming the career barriers to women in broadcasting.

I heard you mention on Elizabeth Day’s How To Fail podcast, that your relationship with money has changed over the years. How so?

“When I was young, it was all very stupid. It was all tied-up in believing in things like ‘fate’ and ‘destiny’, which is utter rubbish. You should never do that. You’ve got to be down-to-earth, practical and only believe what’s [proven to be] true. Don’t be fooled: anything that seems too good to be true, is too good to be true, so don’t believe it. People are always trying to sell you something amazing. I must have been conned into who knows how many insurance policies and all sorts, because I was young and naive and believing. Be very suspicious, be very, very careful [when it comes to money].”

“I realised the most important thing in my life was freedom and that you do need a certain amount of money to be free”

What caused you to change your view around money?

“A lot of it was to do with growing up, probably. I was never money orientated. When I decided I wanted to be a journalist it was the idea of adventure. I was never driven by ‘what is the top earning job?’ It felt a bit wrong. I was terrified of doing a boring job. Terrified.

“Here’s a good example of my ‘badness’ with money. When I was in school, you often had a holiday job and a January sales job, across the Christmas holidays. I worked in C&A in Kingston-On-Thames and we got jobs as sales girls. They were mostly hideous creations. These women would come into the cocktail department and try these things on and say, ‘What do you think?’ I would be honest and say, ‘Actually, I don’t think it suits you…’ At the end of the week we’d get our money in a little brown envelope and all the sales girls were absolutely shocked that I had made the least commission of anybody. It was big indication to me that selling things was not my strong point!

“Then as life goes on, I realised the most important thing in my life was freedom and that you need a certain amount of money to be free. At the moment nobody’s going anywhere much, but if you want adventures, you need a certain amount of money. So I’m not driven by it, but I’ve realised you’ve got to be sensible and don’t waste it – like I used to.”

Hey, hi, hello

You were famously the first female presenter on Radio One. What advice do you have to women, or anyone facing discrimination, about entering the creative industries?

“I think just don’t accept rejection. You may get rejected several times. I used to think that meant you can’t go again, but it’s not true. Some boss at the top might change jobs or policy or change their minds, you never know, you’ve got to be consistent. But also accept that no one has any entitlement to any job at all, so it’s up to you to make it work and make it happen. For me, it took three years to get in at Radio One and the weird thing is that there wasn’t another female DJ for 12 years. That’s the bit I never understood. I had no idea whether there were any more who wanted to do it and got turned down or not. I still don’t know. All the people who were in control then are long gone…”

That does seem to be a pattern. There’s often a trailblazer, but it’s a long time before people start to come through without encountering that discrimination.

“Yeah. You think, ‘Was it a token gesture?’ It was a lot of pressure [on them], some of it generated by me, the feminism movement was growing… But I also think it’s what I call the ‘You’ll do syndrome’. If you hang in there and suddenly someone is ill, or people are on holiday and they go, ‘Oh god, who do we know?’ You’ll be the one who comes to mind. In all kinds of ways, not just broadcasting.

“A lot of people got the opportunity by just hanging in there and it’s important for me that women are in broadcasting because of their talent, not because of gender tickboxing. I think now they are. There are so many really good female broadcasters. Now the situation is much, much better and we have people at Radio 1 I’m very proud of. You want to be there because you’re accepted as good enough to do the job, not because you ticked a box. We all want to feel we’re there for the right reasons, not because of some quota.”

I know someone who started at the BBC and there were three women and one guy in the same job. They’ve all since had kids, but it’s the guy who is now a producer and still full-time, whereas the three women are now part-time or in the same position. This is not to suggest the BBC is at fault. It seems to happen everywhere, but it neatly illustrates how disproportionately women with children face reduced earning power and opportunity in the creative industries.

“I feel very strongly about this. I was bringing up small kids when I joined Radio One. I’m very aware of that situation. It’s about how we help women through those years. They need to retain their confidence and abilities and keep up with the technology, so that when children grow up and they can return to full-time, they retain their confidence.

“I remember someone saying at an awards show, ‘Show me a working woman who isn’t guilty.'”

“I know very, very well how that feels. There are a lot of boys with toys who love swanking about with their technology and love to cut you out of that, to say, ‘You don’t understand what this means…’ They want to exclude you and I think women can get very intimidated by that. But you’ve got to keep up with them and stay in the loop. Even if you’re doing one day a week, try to stay in the loop and tick-over, when you’re children are in their early years. Then when they’re older, they can come back with great force. I’ve seen a lot of people do that. You see women, when they’ve been caring for a child for all those years, actually gain a lot of confidence, because it’s not easy to bring up children! It’s much easier having a job.”

Don’t write yourself off

“I remember someone saying at an awards show: ‘Show me a working woman who isn’t guilty.’ It is really difficult, you know? You don’t want to miss the carol service. But I think a woman who is fulfilled with work and childcare is going to be a happy person, the trouble is getting the balance right. When you’re hot, you’re hot. If someone’s saying, ‘Oh come to New York this week and then we’ll go to LA…’ And you’re thinking, ‘I can’t do that. Am I going to miss out? Someone else will get that job and I’ll be overlooked.’

“I wish we could find a way to organise [to do something]. We had a thing called Sound Women, Jane Garvey, me and Angie Greaves (among others) who are three women broadcasters, which was trying to support women in broadcasting. Eventually, it was broken up, but it was a very good way of meeting women in broadcasting. I remember one of them saying to me, ‘I do a breakfast show.’ And I said, ‘Who drives the desk?’ and she said it was a bloke. I said, ‘Change that immediately.’ Because he’s got the power and you’re not going to be respected equally if you don’t have the same technical ability. I felt that so strongly. If the guy’s got control of the desk, he can fade you out any minute. Things like that, if you’re a woman you’ve got to have the confidence to stand up for yourself without [worrying about] being called some horrible bitch.”

Clearly, we really need solutions that allow women to work without the guilt. Childcare is a huge part of that.

“It’s been a problem for women as long as I’ve been doing what I do. I’m very aware of it. So don’t write yourself off. Don’t think, ‘I’m not 23 anymore, I won’t be able to keep up.’ You’ve got life experience. You might be much better with people, for instance, than someone who’s had their headphones on for 25 years and never held a conversation, which happens!

“Journalism and broadcasting seem to be quite necessary at the moment. People need us. We have a role to play and I’m very grateful for that”

“Women make good communicators, good producers. I work with all women. I can’t remember the last time I worked with a man. It wasn’t a decision, it was just the way it happened at Radio One. I’m not anti-men, it’s just there’s a kind of division. They often seem to prefer the tech-y side and email speak. Some people have spent their whole lives in front of the computer and don’t remember what it’s like to talk to real people. I’ve really enjoyed promoting this book because I’ve had so many good conversations with people like yourself. I’m really enjoying it. I’m enjoying this, you know?”

I’ve got kids now and I’m still freelance and I go back and forth a lot on whether I should be doing ‘a proper job’ somewhere, to support the family…

“But what is ‘a proper’ job?”

Well… Exactly. I don’t know! But I think it’s the conversation that I’d struggle to give up. Essentially, I need people like you, Annie, to solve my problems.

“Ah! Well I don’t know if I can do that. I can talk your head off, though! Frighteningly so. I love having conversations, but I also think to be honest that we’re incredibly fortunate at the moment to have any kind of job in communication. I don’t want to scare anyone but we don’t know where this thing is going, so my sense is work very hard, be very conscientious and be very grateful. Thankfully, things like journalism and broadcasting seem to be quite necessary at the moment. People need us. We have a role to play and I’m very grateful for that. You see the headlines: 12,000 jobs go at Marks & Spencer, or British Airways. You think what are those people going to do? So I feel pretty privileged. I think we’ve got to help each other. But I think it’s talking to other people that has kept me going.”

Annie Nightingale’s latest book ‘Hey Hi Hello: Five Decades of Pop Culture from Britain’s First Female DJ‘ is available now via White Rabbit.

How I Make It Work is a series of interviews with a variety of creative professionals, where we discuss personal experiences and lessons learned about money in the creative industries.